With more than one-third (34.5%) of the annual U.S. corn crop used in the production of fuel ethanol, sooner or later, declining production of ethanol will be felt by corn growers; not necessarily a good trend for ag equipment makers or dealers.

Fortunately, production is not expected to decline much. Plateauing, with little or no growth, is probably much more likely. The recent spate of exception waivers approved by EPA is also a matter of concern to corn growers.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) 2019 U.S. Fuel Ethanol Plant Production Capacity report, released on August 26, fuel ethanol production capacity in the United States totaled 16.9 billion gallons per year (gal/year) or 1.1 million barrels per day (b/d), as of January 2019.

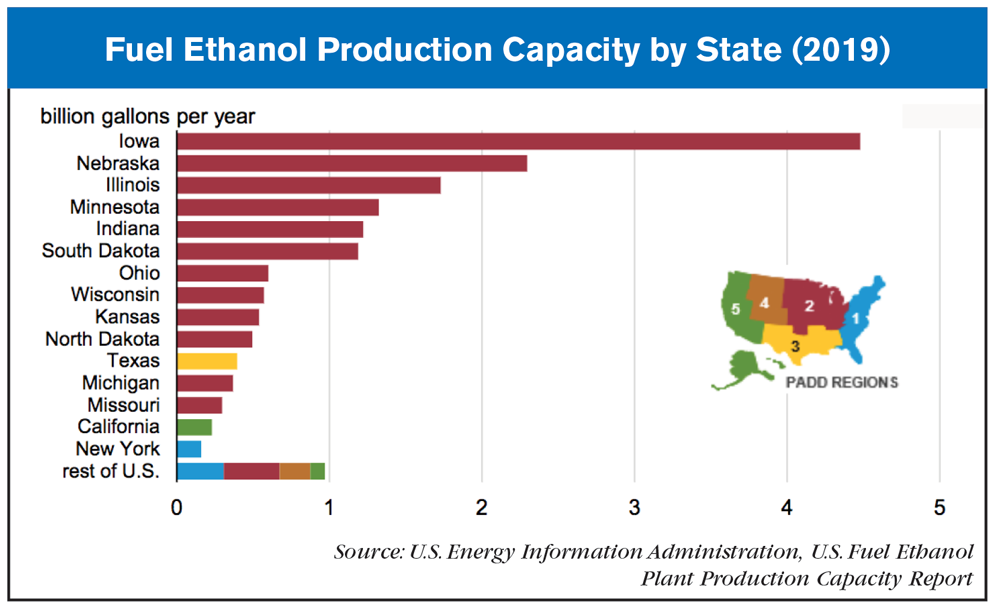

Most U.S. fuel ethanol production capacity is located in the Midwest region (Petroleum Administration for Defense District, or PADD, 2). This, of course, is the heart of the country’s major cropping region. Total nameplate capacity (installed capacity) in the Midwest totaled 15.5 billion gal/year (1 million b/d) at the beginning of 2019, an increase of almost 3% — more than 400 million gal/year — between January 2018 and January 2019. During the same period, combined fuel ethanol production capacity in the East Coast and Gulf Coast regions (PADDs 1 and 3) decreased by more than 100 million gal/year.

Of the top 13 fuel ethanol-producing states, 12 are located in the Midwest. The top three states — Iowa, Nebraska and Illinois — contain about half of the nation’s total ethanol production capacity.

U.S. production of fuel ethanol reached 16.1 billion gallons (1 million b/d) in 2018. In the September Short-Term Energy Outlook (STEO), EIA expects U.S. production of fuel ethanol to decline slightly to 15.8 billion gallons for 2019 because of poor market conditions for ethanol producers and oversupply issues.

Exception Waiver Politics

On Aug. 9, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced that it had approved the 2018 exception waivers for 31 small petroleum refineries and denied 6, an approval rate of 83.7%. The decision received immediate backlash from both farmers and ethanol advocates

Geoff Cooper, CEO of Renewable Fuels Assn., said in a statement, “At a time when ethanol plants in the Heartland are being mothballed and jobs are being lost, it is unfathomable and utterly reprehensible that the Trump Administration would dole out more unwarranted waivers to prosperous petroleum refiners.” Smaller refineries disagreed. In a statement, the Small Refiners Coalition said, “The decision to grant small refinery hardship is a legal decision, not a political one, and we are pleased that [the department of Agriculture’s] influence did not cause EPA to depart from the rule of law.”

As a result, several ethanol producers took steps to scale back production following the announcement. World Energy, one of the largest ethanol producers in North America, according to Biodiesel Magazine, announced a production cease and employee furlough at three of its plants on Aug. 16. POET, another large North American refinery, announced on Aug. 20 that it will begin idling a 92 million gallon plant in Indiana “due to recent decisions by the administration.”

The Aug. 9 decision follows an already rough period for ethanol producers. U.S. corn growers have been plagued this year by both a trade war and a late planting season. According to data from Renewable Fuels Assn., growth of ethanol production slowed to an almost flat rate in 2018, following a 19.9% increase in ethanol production between 2013 and 2017. Additionally, ethanol consumption decreased between 2017-18 by less than 1%, following an 11% increase between 2012-17.

The issue of required biofuel blending has been a long standing one. Ethanol and oil producers have competing interests when it comes to biofuel requirements: ethanol producers and corn growers want them higher to increase demand for their product and oil producers want them lower to reduce costs.

Despite the tradition of the battle, tensions had risen extraordinarily between those in agriculture and the EPA leading up to Aug. 9. EPA set biofuel-blending usage targets for 2020 in July 2019 with a goal of 20.04. billion gallons (a 0.6% increase from the 2019 targets, according to Bloomberg) but failed to answer for how often they would grant exception waivers from these biofuel-blending requirements to smaller refineries. These waivers, according to SafeHaven, effectively remove some smaller refineries’ obligation to purchase ethanol, should they successfully make the case that it would be too much of a financial burden.

In response to these released goals, Lynn Chrisp, president of the National Corn Growers Assn. (NCGA) said, “We are frustrated the EPA did not account for potential waived gallons going forward in the proposed rule. If the EPA continues to grant retroactive waivers, the Renewable Volume Obligations (RVO) numbers are meaningless.”

Soybean growers were also disappointed that the EPA, in the same July 2019 announcement, did not raise biomass-based diesel volume requirements for 2021, of which soybeans are a large component. In a statement, American Soybean Assn. (ASA) president Davie Stephens said, “The [July] proposal doesn’t reflect the needs and capabilities of the domestic biodiesel and soybean industries and doesn’t seem to reflect President Trump’s stated support and commitment to domestic biofuels and a strong Renewable Fuel Standard.”

The refusal to answer on their wavier approval methods in July ended up being a foreshadowing of the Aug. 9 decision, in which the EPA denied the most exception waivers in the past 3 years at 6 denials, topping the one denial issued for both 2017 and 2016.

Following considerable disapproval, according to Reuters, president Trump met with Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue and EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler on Aug. 22 to discuss possible solutions for ethanol producers and U.S. farmers. Since then, president Trump has discussed several ways to reverse the damage done to ethanol producers, going so far as to “tentatively approve,” according to Reuters, a plan to increase biofuels blending requirements in the coming years.

If this plan is officially approved, the EPA will “calculate a three-year rolling average of total biofuels gallons exempted from the mandates under its Small Refinery Exemption Program” and add that to the annual biofuel blending requirements for 2020. This would bring the projected biofuel blending mandate for 2020 from 20 billion gallons to about 22.4 billion gallons, according to Reuters’ calculations.

The current administration has already made considerable attempts to shore up U.S. agriculture in the wake of a trade war and rough planting season, including the 2019 Market Facilitation Program and permitting the year-round sale of E15 fuel.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment